- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rapidly progressing, incurable neurodegenerative condition caused by misfolded proteins known as prions.

- These prions damage brain tissue, forming sponge-like holes that significantly impair motor skills, memory, and cognition.

- The disease has several forms: sporadic (sCJD), familial (fCJD), iatrogenic (linked to medical exposure), and variant (vCJD), which was associated with contaminated beef.

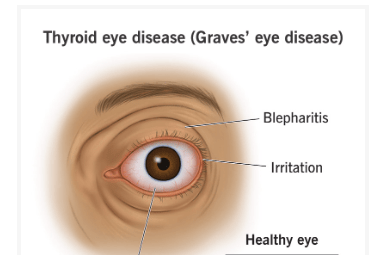

- Common early symptoms include personality changes, memory loss, impaired judgment, blurred vision, and insomnia.

- As the disease advances, patients experience speech problems, coordination loss, muscle jerks, and eventual inability to move or speak.

- Death typically occurs within 12 months of symptom onset, though variant CJD may last slightly longer.

- Variant CJD usually affects younger individuals and presents with psychiatric symptoms earlier than other forms.

- Diagnosis involves clinical assessment, MRI, EEG, and cerebrospinal fluid testing; definitive confirmation requires brain biopsy or post-mortem examination.

- There is no known cure; treatment is focused on comfort, symptom management, and supporting caregivers.

- Reference: Mayo Clinic – Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

The symptoms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease do not appear suddenly. Unlike Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, there is no gradual accumulation or early warning signs that last for years. Rather, it strikes with frightening speed, trapping patients and their families in a vicious cycle of swift decline and unsolved issues. Within a few weeks, CJD’s particularly aggressive nature becomes apparent, despite its initial confusion with other forms of dementia. Although it is an uncommon ailment, its effects are especially severe.

The illness is a member of a larger family of prion disorders. Prions are proteins that have gone rogue, twisting into strange shapes and starting a chain reaction that makes normal brain proteins toxic. They are not bacteria or viruses. The “spongiform” effect—microscopic holes that deprive the brain of its structure and function—is caused by this chain reaction of damage. In addition to having cognitive effects that are remarkably similar to those of other types of dementia, the outcome also happens very quickly.

The emergence of variant CJD in recent decades has caused a public health panic throughout Europe, especially in the UK. The human form of vCJD, which was linked to eating beef tainted with BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), served as a terrifying reminder of the connection between neurological health and food safety. In addition to focusing on younger people, this variation of CJD frequently starts with mental health issues like anxiety or depression before developing into full-blown dementia.

The transition from diagnosis to end-of-life care is extremely stressful for families. The experience of dealing with a disease that takes away speech, mobility, and recognition in a matter of months is frequently described by caregivers as emotionally confusing. Since there is no cure to slow or stop the progression of CJD, doctors are also frequently faced with the limitations of contemporary medicine. There is only palliative care available, with an emphasis on comfort, agitation management, and physical pain alleviation.

Scientists are examining the mechanics of prion diseases in order to identify possible biomarkers and develop future treatments by working with global research initiatives. However, collecting reliable data is still difficult due to the rarity of CJD, which is estimated to be 1 to 2 cases per million annually. However, significant advancements in early detection techniques utilizing imaging and spinal fluid have made it possible to diagnose before irreversible brain damage has occurred.

Stories of young patients, such as Jonathan Simms, whose family pushed for experimental treatment in the early 2000s, have raised public awareness of ethical discussions surrounding medical innovation and end-of-life care. Despite its unusual conclusion, his case generated discussions about patient autonomy and access to experimental drugs around the world.

Additionally, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease leaves a cultural mark, posing more profound queries regarding the complexity of the brain and the frailty of the body. CJD serves as a reminder that even proteins—molecules essential to life—can become dangerously misdirected, in contrast to diseases brought on by lifestyle choices or external infections. As neurological research advances in the upcoming years, prion diseases might provide information about both uncommon and more prevalent neurodegenerative diseases.

CJD is rarely known to the general public until it affects a well-known person or makes headlines due to a health scare. However, its effects extend well beyond news stories. The illness pushes the limits of diagnosis and treatment for the medical community. It serves as a reminder to society of the importance of empathy, readiness, and strong support networks for people dealing with quickly worsening illnesses.

Despite the lack of a cure, the story of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is not just one of loss; it also highlights the tenacity of families, the quest for knowledge, and the calm, focused care that marks a dignified end to life. Even in the face of a disease that kills people relentlessly, that human reaction is still incredibly strong.