Von Hippel Lindau disease acts more like a shadow that stealthily weaves itself through a family’s history than it does like a conventional illness. VHL affects many organ systems, tying together benign and malignant tumors across the brain, eyes, spine, kidneys, and adrenal glands. It is frequently only identified after years of mild symptoms. Similar to a gardener pruning back an overgrown vine that won’t stay contained, patients describe it as a lifetime of interconnected challenges that require constant vigilance.

VHL is caused by a genetic mechanism that is surprisingly straightforward. The disorder may manifest if you receive a single copy of the mutated VHL gene from either parent. Cells lose their braking mechanism and begin dividing uncontrollably, which sets off a cascading effect. Despite the fact that this mutation is autosomal dominant, up to 10% of cases manifest without a known family history, making the onset of the disorder both surprising and predictable.

Von Hippel Lindau Disease – Key Facts Table (For WordPress)

Reference: Cleveland Clinic

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Condition Name | Von Hippel Lindau Disease (VHL) |

| Classification | Genetic disorder, autosomal dominant |

| Organs Affected | Brain, retina, spinal cord, kidneys, adrenal glands, pancreas |

| Common Tumor Types | Hemangioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, pheochromocytomas, pancreatic NETs |

| Typical Symptoms | Vision changes, headaches, balance loss, hearing issues, fatigue |

| Diagnostic Tools | Genetic testing, MRI, CT scans |

| Most Effective Treatments | Tumor resection surgery, targeted therapy, monitoring |

| Genetic Risk | 50% chance of inheritance if one parent carries the mutation |

| Estimated Prevalence | Approximately 1 in 36,000 people globally |

| Recommended Resource | Cleveland Clinic VHL Page |

The amount of guesswork required to identify VHL has been greatly decreased over the last 20 years due to developments in imaging and molecular diagnostics. Before a genetic test was finally recommended, patients would alternate between neurologists and urologists. Healthcare teams can now identify tumors early, sometimes even before they cause symptoms, thanks to proactive screening and family history mapping.

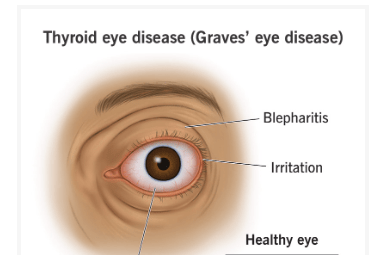

The first obvious symptom of VHL is frequently retinal hemangioblastomas, which can occasionally be identified during a standard eye exam. For many patients, losing their vision is a warning sign of more serious systemic problems rather than just a minor inconvenience. With prompt laser therapy or surgery, retinal damage in VHL can frequently be lessened, but if left untreated, it can result in permanent blindness. Early detection is therefore especially advantageous.

Clear cell renal carcinoma is among the most worrisome outcomes in VHL. This aggressive type of kidney cancer develops in between 25% and 60% of VHL patients. In contrast to sporadic kidney cancers, kidney cancers associated with VHL are frequently bilateral or multifocal and affect younger people. Nephron-sparing surgery, however, can be used to treat these tumors with regular monitoring, maintaining kidney function while removing only the malignant growths.

Managing a genetic condition like VHL can have a devastating emotional toll. According to some patients, it’s like living under a never-ending MRI schedule, constantly anticipating what the next scan will show. Many people find strength in community—making connections with others through forums for rare diseases and patient networks—despite the stress. These areas have developed into lifelines, providing much-needed empathy and helpful guidance.

The strong appreciation for physicians who take the time to explain not only the science but also the strategy is a recurring theme in the experiences of VHL patients. Patients’ future planning is altered when they learn that pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors may remain stable for years or that cerebellar hemangioblastomas may impair balance. There is control in that clarity, and control is a powerful tool when dealing with a chronic illness.

Genetic counseling is essential, particularly for young adults who are thinking about starting a family. Determining whether to test children or wait until adulthood is a very personal decision. While some people wait until symptoms manifest, others favor early intervention. In either scenario, having a qualified counselor present makes the process less intimidating and incredibly transparent regarding risk and preparation.

Remarkably, high-profile medical dramas and celebrity campaigns about genetic awareness have even brought VHL into the public eye. Even though not many public figures have publicly disclosed VHL diagnoses, the media’s storytelling trend has contributed to a change in the way rare genetic conditions are viewed—not as isolated anomalies, but as problems that link ethics, science, and human resiliency.

From a research perspective, VHL still has an impact on genetics and oncology. By using the VHL mutation as a model, researchers looking into tumor suppressor genes have been able to understand how cellular growth becomes unchecked and how to restore order to that chaos. Particularly cutting-edge treatments that could eventually be customized for each patient’s genetic makeup are being fueled by these discoveries.

Beyond its effects on medicine, VHL influences discussions about healthcare equity in society. Particularly in areas with limited resources, regular MRIs, access to genetic counselors, and qualified specialists are not always covered or available. Because of this discrepancy, results can vary significantly depending on one’s location and insurance status. It takes more than just medicine to close that gap; it also requires a dedication to equitable healthcare access.

Some hospitals are beginning to implement remarkably successful case management programs. Care coordinators are assigned by these programs to oversee appointments, monitor imaging, and assist families in knowing when and how to respond. For many people with VHL, this proactive approach has significantly improved long-term results.